Annotated 23-7

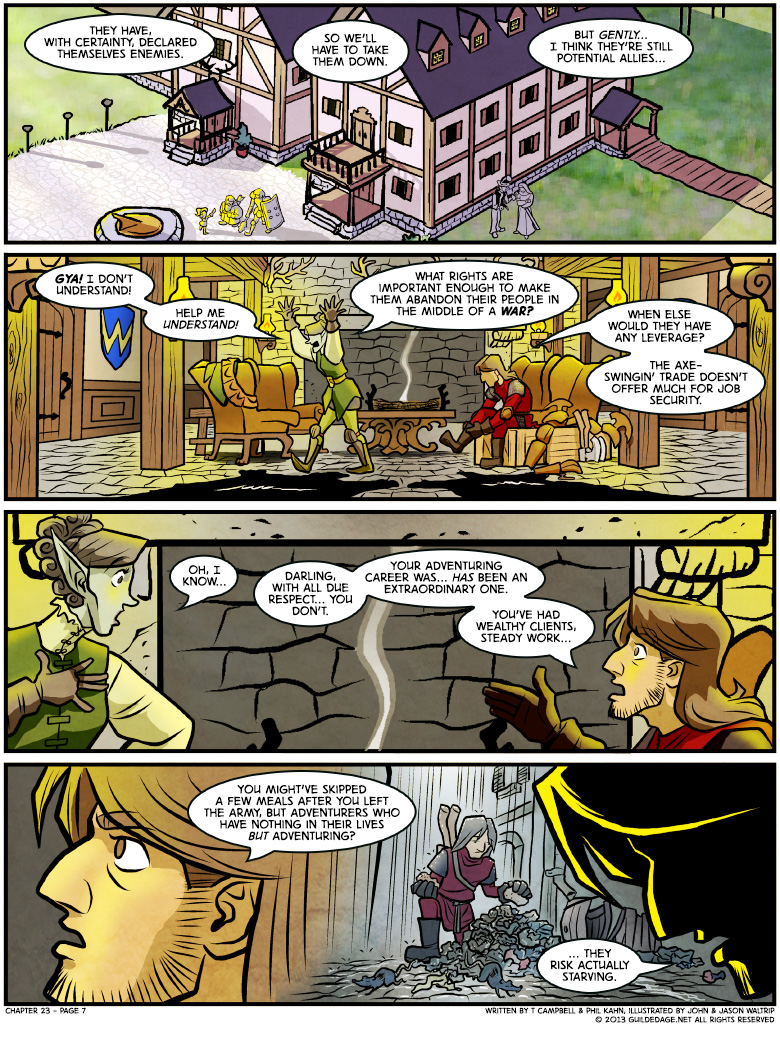

For once Byron is more politically informed than his varryn-mate. Check yo’ privilege, Syr’Nj.

For once Byron is more politically informed than his varryn-mate. Check yo’ privilege, Syr’Nj.

At this time, I was perhaps as well-equipped to write this scene as I ever would be. Compared to many, I have had an easy life. My reasonably successful parents have always been there when I needed them, emotionally or financially. But I was far too old to be comfortable relying on them, was trying to make it on my own, and by most measures, was failing dismally.

The Liberty Tax office in my area had fired everyone on staff except me, due to some interpersonal drama I had mostly avoided. This meant I had a temporary gig with more than 40 hours a week of work, and more and more as April 15 and May 1 approached. And I worked as many hours as they gave with the knowledge that soon after those dates, I’d be out of a job completely. On top of this, I had two months to find a new place, as it became clear that one of my oldest friends and I just did not work as roommates. I still wasn’t really financially desperate, but I was thinking like I was, enough so that when Byron says “actually starving,” I could hear the grit in his voice.

I held my tongue yesterday and Syr’Nj is basically me, withholding judgement in public but privately considering them traitors, and wondering what to do. Even as traitors they can be talked down from their “silly” position, right? Killing them is obviously ridiculous, but surely their cause is unjust, right?

Faith in the system crumbles when one sees people destroyed by it.

All rebellions are illegal, until the rebels win (resulting in either a coup and usurpation of authority under the existing system, or revolution if the system is what they’re rebelling against), or a more powerful authority grants them legitimacy under terms they’ll accept (in which case they either legally constitute expatriates, traitors, or ex-rebels – something along those lines).

Technically, though, every nation defines treason and traitorship differently – in the U.S., treason is legally harm to the country by betrayal to its enemies (something a traitor would do, essentially selling out the country’s people, operations, or upper hand, or simply aiding the enemy in a legitimately benign manner, and even if they’re the underdog), whereas in a monarchy it tends to also (or even only) include acts against the monarch themself (and it’s very easy to disagree on whether something that harms them is something that harms the country; just look at revolutionary France).

Of course that’s also just the legal perspective; the citizenry may have other views on what constitutes treason, especially if they’re prone to vigilantism or have morals that don’t align perfectly with the law (whether they’re oblivious or not is irrelevant). It’s sort of a popularity contest on that level; many are loyal to office holders, while others are loyal to the office itself, and still more don’t recognize the difference between the two.

And then of course, back to the legal perspective: who actually are the country’s enemies? Selling out your country to a technically neutral party isn’t technically treason if the act of treason first requires an official state of war with them to be in force. Doing it with a country that you have a formal treaty with also won’t count, unless they later turn around and attack – which you can claim to have had no foreknowledge was a possibility, if the authorities will buy it.

Of course, if you take the appropriate measures – like renouncing your citizenship, declaring your territory to be in open revolt (or getting your country to do that for you), and then provoke an official declaration of war – then you can technically be considered an enemy of that nation, legally. That seems to be something along the lines of what Rendar did.

And at that point, then, yes, you can start to talk about justification – but there’s still legal matters to consider, and there’s a war on, which efforts to win are, in this case, being hindered by an ex-citizen.

That might be construed as helping the WR, the way our disagreeable head of house above seems to imply it is. But we’ll probably want to hear from a Gastonian legal scholar on that matter, before we decide if it’s a legal or moral betrayal.

“in the U.S., treason is legally harm to the country by betrayal to its enemies (something a traitor would do, essentially selling out the country’s people, operations, or upper hand, or simply aiding the enemy in a legitimately benign manner, and even if they’re the underdog)”

Or actually making war against the United States.

United States citizens who go to war with the USA have committed treason, which sounds a lot like what the Fightopians are doing. That is, unless an American renounces their citizenship in a way that’s legally recognized, war against the government is punishable by death; declaring yourself citizens of an unrecognized nominal state doesn’t cut it.

In a practical sense, though, any cause that gets enough support to qualify as a “war” probably has enough support that just killing the ringleaders is unlikely to fix things, and quite likely to inspire a new batch of troublemakers.

All of that’s true in theory, but if a rebellion against the US actually succeeded, the legal question would become moot. Even in the Civil War, not too many Confederates were hanged for treason.

Rebellion is treason, but it only counts as rebellion if you lose. After all, the Founding Fathers would all have been hanged as traitors if they’d lost.

John Harrington — ‘Treason doth never prosper: what ‘s the reason?Why, if it prosper, none dare call it treason.’

As others said, yes, in theory.

The reasoning behind my phrasing was that if you’re equipped to make a declaration of war, that the U.S. takes seriously enough to make you an official enemy, you’re past the point of treason and have effectively gained both independence and sovereignty as a state already.

On paper, at least, the U.S. does not make war against non-state entities. To actually declare war against them would require there to be a legal means to do so, and war is officially a conflict between state entities under our legal system – there is no mechanism to declare war against any other entity.

The reason there is no mechanism is because the U.S. Constitution was written as the constitution of an isolationist state, that was not intended to get involved in external conflicts, especially not ones involving other nations – to make war only as a last resort, when we are under a clear and present threat from a foreign power.

Domestic and international “terrorist” groups are some real-life examples of non-state entities that the U.S. has had to stretch the Constitution just to engage in combat against (and we have actually exploited this gray area as a loophole, as well, to avoid provoking conflict with the existing state entities they tend to target); we call that the “war on terror”, colloquially, but there’s no official definition of such as a war to cite, in the history books.

Even if there was, it would be at odds with the literal interpretation of our founding document, which, again, essentially defines the declaration of war as a power Congress can use against a hostile state entity, to open up the floodgates of government funding and authorization (for the Executive Branch to use) for all sorts of retaliation.

So to reiterate, declaring a war on a hostile non-state entity would be equal in function to recognizing it as its own state, under U.S. law, which would grant it a sort of legitimacy that nations like the U.S. do not grant lightly – for the obvious reason of it bolstering the morale and unity of the actors involved, and creating inroads for existing foreign powers to foster it into its own sovereign power (or, a stable state it can control). (And, as mentioned, so that we don’t provoke foreign powers by granting those non-state entities recognition that the foreign powers refuse to.)

It’s never been true that the United States doesn’t make war with non-state actors, though. Extraordinary executive power, particularly the suspension of habeas corpus, is explicitly granted to suppress rebellion. A United States citizen making war against the government is explicitly listed as the definition of treason, before “aid and comfort” to an enemy. Washington took 13,000 soldiers to put down tax rebellions in Pennsylvania.

And, of course, there’s the big one, 1861-1865, where the federal government waged war against rebellious states in its own territory, without ever recognizing the Confederacy as a legitimate government. Legally, the United States were at war with a collection of rebellious state governments, and the draft, the taxes, and the Emancipation Proclamation were all put into place without recognizing the belligerents as a sovereign power.

JamesK is correct, of course, that no Confederates were punished for treason. Andrew Johnson signed an unconditional pardon for all of the rebels who fought in the war, specifically for the offense of treason, in 1868. Legally, every commissioned officer and government official who’d taken up the fight against the government was clearly guilty of a capital offense.

Yeah, not discounting other “political violence” or claiming it doesn’t exist – but we just never call it “war”, and those were the reasons. And that results in the law being applied in somewhat unintuitive ways.

It’s kinda similar to how economic crimes tend to be labeled “fraud” or “embezzlement”, but almost never as a “conspiracy” – you’d have to indict the majority of the economic system if you tried to do that, because a good amount of those crimes are only possible in a lot of cases as a consequence of the delegation of authority, company structuring, and fiscal shenanigans that businesses routinely (and legally must) engage in.

That’s my perspective on the matter, anyway, after having studied what happened in 2008 and what’s going on now.

The US was actually very careful not to declare war on the Confederates officially, but then it began the anaconda strategy and cut Confederate trade by setting up a blockade on the Atlantic and Mississippi. Blockades are an act of war, which recognized Confederate existence as a foreign nation. This would have allowed legal international intervention by foreign nations (something the Confederates banked on). Britain and France almost intervened— Britain because of their cotton imports, France because of their designs on Mexico. Eventually it was decided to be too costly (and also British people didn’t like slavery, its why Lincoln made the Emancipation Proclamation and why he has a statue in Manchester).

To relate this back, “police actions” are fine against rebels/terrorists while “acts of war” can invite opposing foreign interference. Gastonians aren’t too worried about that since there aren’t too many other countries. The Wood Elves, Gnomes, and Sky Elves have treaties with Gastonia and also hold no sympathy for Fightopia, while the ‘Savage Races’ are already at war with Gastonia.

Syr’ng sees the big picture since Harky and his followers would see no difference

in Gastonia and Fightopia and lay waste to both sides.

*narrator voice* “The Heads of Houses’ steps to put uppity adventurers back in their place would ultimately lead directly to Syr’nj bringing the rest of the Peacemakers to join the World’s Rebellion.”

And that happens when Penk usurps Harky. Harky wasn’t interested in differentiations.

I don’t get the alt-text. If you catch and eat a rat, won’t you unavoidably get experience for it?

Must be a system where rats don’t drop tiny meats, but you can instead catch the whole rat and put it on a stove to make “roasted rat”.

So you either catch it or kill it.

Bandit, Frigg, Gravedust not tagged.

Good catch!