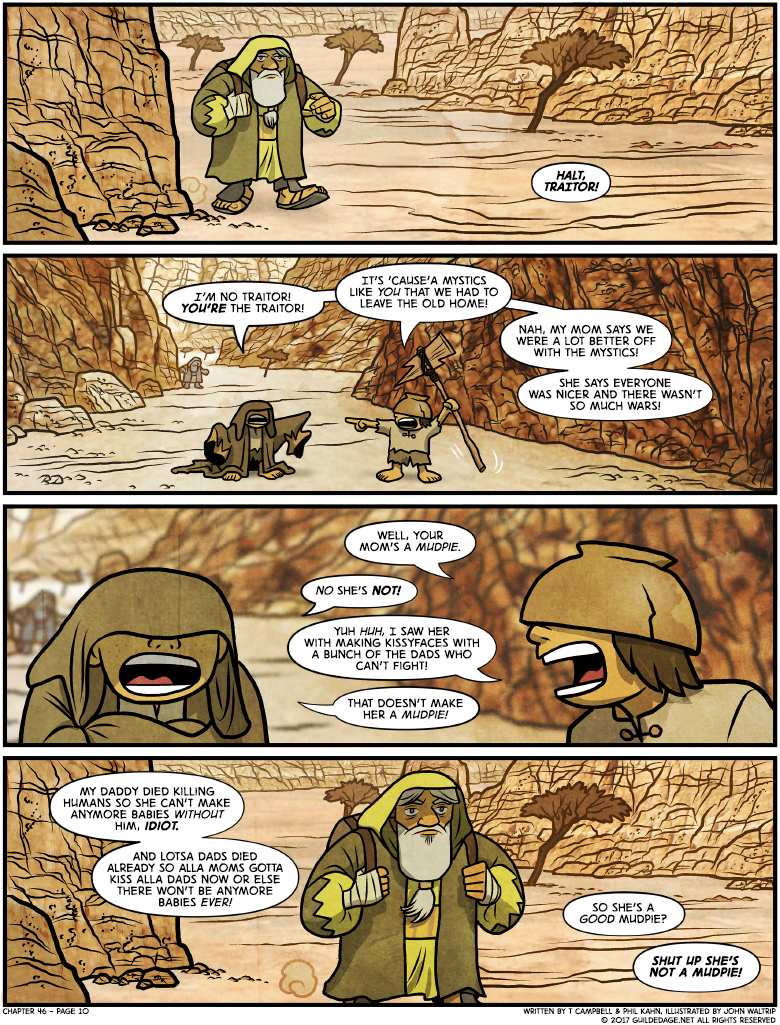

Annotated 46-10

FB: Changing Cultural Norms and the Varying Effectiveness of the “Yo Mama” Joke: A Longitudinal Study

FB: Changing Cultural Norms and the Varying Effectiveness of the “Yo Mama” Joke: A Longitudinal Study

This was an outgrowth of my general observation that a lot of the early Bible is a complex survival guide for desert-dwellers. A lot of its seemingly arbitrary rules start making more sense when you realize that not following them could cause your tribe its collective demise. I don’t mean that in some kind of conservative, moralistic, won’t-someone-think-of-the-children way. I mean that it really was almost impossible to keep and care for a pig in desert conditions in a way that would give you a hygienic meal, so you might as well just call the animal “fundamentally unclean” and save yourselves some food poisoning and worse.*

*Edit to add: this subject has advanced some since the last time I looked at it in depth, see the comments. However, I would maintain that many old cultural norms do have their roots in what helped older cultures survive, or at least those cultures’ best understanding of what helped them do so.

So what happens when the rules of survival change? A number of different things, but you end up with a culture that’s torn between old and new ideas, uncertain of itself and its identity.

You would think a miraculous animal such as the pig would appeal to religious folks. FFS, it turns garbage into bacon. If that does not at least give one a momnet’s pause regarding the possibility of a powerful being, I don’t know what will. :-)

Heck, even today we have a lot of people who have hard time letting go of old wrongs and rights… Even to point where neither accuser nor the accused had anything to do with the things one is being accused of.

But can we just appreciate the fact that ol’ Gravey must have taken almost no steps to get away on his soul searching quest and he’s already confronted by to and fro about exactly the thing that bothers him. How (un)lucky can you get? :D

The “trichinosis” explanation for the Torah’s prohibition of pork has long been debunked. If it were true, then by the same reasoning, beef would also be forbidden due to the risk of E. coli poisoning, as well as poultry and fish for the danger of salmonella poisoning.

Furthermore, most instances of food poisoning can be averted by thoroughly cooking the food and then either consuming it immediately or preserving it with smoke, brine, or other reliable methods. All of this was known to people via observation, many centuries before the discovery of a single microbe, let alone Pasteur’s linkage of microbes with disease.

Other theories as to the rationale for the Torah’s dietary laws have been around for some time too. One is that certain meats, such as pork, may originally have been prohibited for the same reason beef is prohibited in Hinduism: the animal, in the dim distant proto-Israelite past, originally was considered sacred and therefore off-limits. Plausible, but in the absence of any archaelogical evidence for pig-worship in Canaan we can’t say for sure.

Another theory does jive with your point about survival of the tribe, albeit survival in the sense of “preserving the distinct tribal identity” rather than “not dying from bad food.” In this view, the whole “these animals are kosher, those are not” classification was arbitrary; what mattered to Israelite cultic leaders was the end result: making it difficult for Israelites to share meals with other cultures and thereby mingle so closely with them so as to assimilate into those cultures. Leaving aside the issues such tribal wagon-circling may or may not create, this strikes me as a more plausible explanation.

In the end, however, we just don’t know why some foods are kosher and others aren’t.

Or anthrax for beef.

Yeah, I think the best explanation for pork taboo is a mix of “eww, pigs eat gross stuff” and tribal identity.

I’m pretty sure e.coil poisoning was never a major problem in cows before modern factory farming conditions led to them being covered in feces all the time.

It not just the pigs

Leviticus 11:7

But look at how they are presented: if it has cloven feet but doesn’t cheweth the chud or vice versa it is unclean. So cloven feet and cheweth the chud = ok. Maybe even not cloven feet and doesn’t chew the chud = ok (not a bible scholar, maybe it is banned somewhere else), but no crossing of those cathegories. I think it is somewhere close that clothes made of two or more different fibres are banned. I believe anthropologists sees taboos against things that are in overlapping cathegories as quite common.

As humans we tend to sort things into different cathegories. For a modern example, a toilet bowl is unclean. So to most people even a toilet bowl direct from the factory, never used as a toilet bowl, never even plugged in, is still a bit unclean. And if someone ate out of a toilet bowl it would cause feelings of something being wrong, because food has to be clean.

This doesn’t contradict more utilitarian explanations, just that all rules doesn’t have logical explanations.

This is a greatly interesting topic that I could only really glance at in this writeup, and your reply, Alice’s, and others have taught me some things. But specifics aside, I think it’s true that a lot of cultural and religious rules have roots in what was once utilitarian good sense for the larger group. A lot of the problems kick in when those enshrined rules run up against the changing needs of the population.

Additionally, most birds are acceptable. If it eats carrion, it’s bad. If not, I think it’s okay? And you can, I believe, eat locusts. But not other insects. Also no reptiles of any kind. Food must be prepared in such a way that dairy and meat are not cooked together. Specifically that prohibition comes from not boiling a “kid in its mother’s milk”, I think, but has been expanded? You also cannot have a leaven in breads, it’s considered an impurity. I looked into Kosher (literally “clean”) requirements a while back but can’t say I remember it terribly well.

You are correct about clothing of mixed fibers. In not food categories, women are unclean for after starting a period, and then only become clean again if they bathe. But not before 7 days have passed or they’re still unclean and cannot be touched without passing that status. Thats… getting off the food topic, though.

Clannishness seems incredibly likely considering old Hebrews had admonishments for marrying outside the tribes.

Reading that, it kind of seems to me like these rules might be a lot older, from a time when people were trying to figure out which berries are fine and which are poisonous. Possibly mixed with some generous “better safe than sorry” stuff. Eating camels, I suppose, is also generally a bad idea because you might need them for transport and milk, and if you eat all your camels, you haven’t got any. Of course, you could breed more, but what if there’s a drought, and not enough to eat, and your people eat all the camels? Also, if you ride it, you maybe wouldn’t want to eat it. Kind of like horses these days, or donkeys.

Some random thoughts about pigs: I’ve been reducing my meat intake for some time now (almost vegetarian by now), and and it doesn’t take too long until the smell of pork becomes rather unpleasant. Also not sure if they’re a particularly good choice in an arid, hot area, especially if you tend to move around a lot. So maybe it’s more of a “cattle is better than pigs” thing, and by getting everyone to avoid them, you spare yourself some annoyance.

Pigs can cause all of those diseases and more. That argument also assumes the diseases present in the ancient world were the same as the ones we have today, but we know that’s not the case. E. coli in particular changes rapidly and many of the the current pathogenic strains are only a few hundred years old. Pigs have much worse hygeine than cud chewing ungulates, which are the only mammals permited to be eaten, and thus are much more likely to spread disease not just to those who eat their meat but through simple handling.

Another theory is that said desert-dwellers cooked over fires made from dried camel dung, whose flames wouldn’t heat dinner to the extent required to kill the disease-causing bacteria more commonly found in certain meats.

Actually, having observed some habits/beliefs/ways of people in different European countries, particularly about housing I’m starting to think that most “generally accepted ways of doing X” are not because people are smart and choose the “best” option for their situation. It’s mostly some people who have tried something and either had a good or a bad experience, and most others sticking to the more successful paths.

Example: In England, most home owners seem to believe that double glazing and non-leaking windows cause mould. That’s because of all the old 1850’s brick houses with a single layer of bricks for insulation regularly get condensation on their leaky single-pane windows, which are even worse for insulation. If you replace the windows, the coldest part of your home is now that one corner behind the couch, and that’s where you get mould. In other places (e.g. Germany), the first people to use double glazing knew what they were doing, and used enough insulation on the walls so the windows were still the weakest point. Overall much less condensation, less ventilation needed, less heating power, better room climate … everything better.

…and then came people who used cheap styrofoam (which is impenetrable to moisture) for even more insulation, and suddenly even their nicely-insulated homes got mould because even what little excess humidity they had couldn’t go anywhere. And suddenly, a number of German home owners are against insulating beyond 1990’s standard because of mould*. So they weren’t actually smarter than the British ones, they just accidentally got it right in the 1970s/80s.

If error is expensive, trial & error becomes a very bad strategy to find good solutions, but trial & error is still the main strategy for most people, for most things.

So we don’t know why the old Hebrews decided to ban pork (or why Hindus decided to declare cows sacred, for that matter), but I suspect they may not have made a particularly conscious choice rather than just sticking with what they already knew worked.

(*) of course, we know that the secret to making it work is either to allow humidity to diffuse through your walls at a low but sufficient rate (i.e. any humidity on or in the wall will dry off quickly enough), and/or to have forced ventilation, where inside air is slowly replaced, but not without passing its heat on to the incoming fresh air, with appropriate measures to capture and remove any water that condenses in the heat exchanger, as you would in an air conditioner.