Annotated 27-6

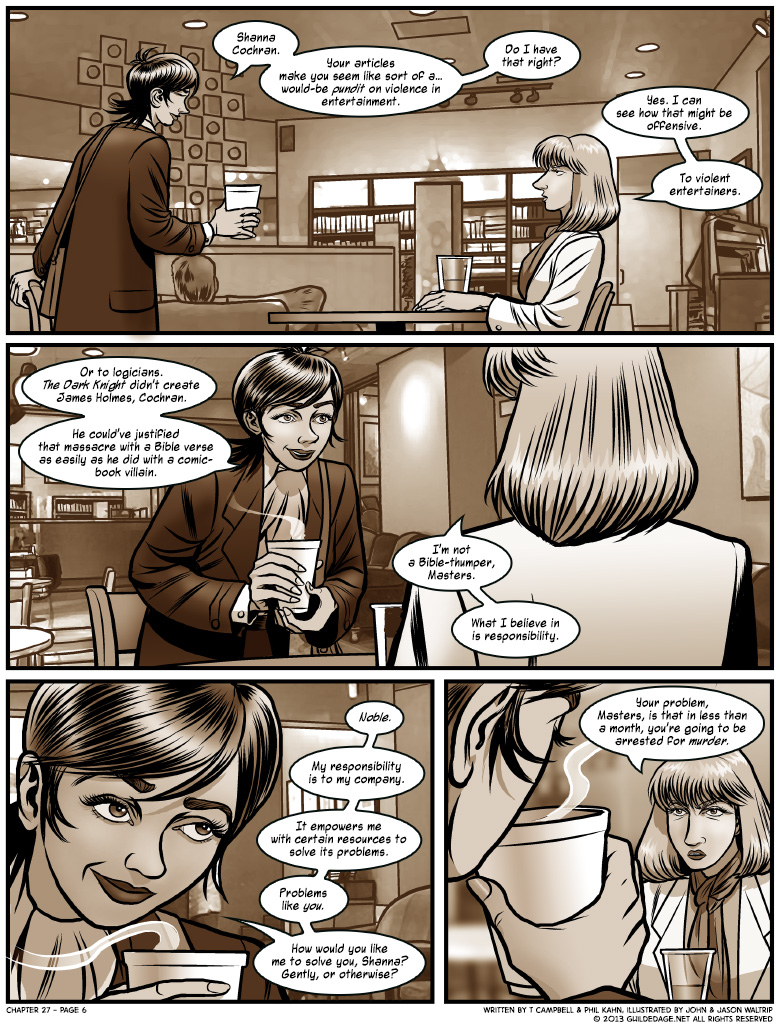

Having knocked Shanna off her feet, Carol presses her advantage, striking at her opponent’s weakest point: her career as a fun-hating puritan, and the notion that such biases may be coloring her current investigation.

Having knocked Shanna off her feet, Carol presses her advantage, striking at her opponent’s weakest point: her career as a fun-hating puritan, and the notion that such biases may be coloring her current investigation.

There’s a conversation worth having about our fiction addiction and the ways it can be unhealthy, and I appreciate the times that Shanna gives voice to that. And you might think her brand of sarcasm would find its own fandom; negative criticism is, as Anton Ego says, “fun to write and to read.” But until she actually spends time with the people she’s critiquing, she will always take that shit too far. That’s mostly due to some personal issues we’ll be getting into later.

Unfortunately for Carol, Shanna is used to being disrespected and condescended to. She may even thrive on it at this point. And it certainly isn’t going to distract her from the facts of this story.

Part of me gets depressed that popular culture has almost forgotten James Holmes, the mass shooter who slaughtered an Aurora theater showing The Dark Knight and called himself the Joker. I wish he still stood out as a particular example of depravity, but we’ve had too many mass shootings since. But on the other hand, people like that deserve to be forgotten, so.

If I remember right, coverage of the trial of the Aurora theater massacre pointedly denied the use of the shooter’s name whenever possible for the exact reason of not giving him satisfaction of the notoriety that he craved.

Yes. It’s also in the journalism best practices for mass shootings to avoid naming the perpetrator or too many details because it has led to copycat crimes.

Where I live, suspects in court cases are not usually named at all in the media, in order to protect a presumed-innocent person from members of the public who might be too quick to judge. People who’ve committed brutal violent crimes/rampages etc. are also not usually named, in order to deny them publicity and avoid making them into some sort of “brand”, and to also spare their family and relatives being publicly associated with the crime. You wouldn’t want some job interview get sidetracked because someone notices you’re a close relative of *that* person, while simultaneously trying to deal with the trauma of realizing that a close relative did *that* thing…

Yeah…. that doesn’t happen too much here. As in the “identity concealment” part. Not in the newspapers I think, but on the local news tv channels is where they don’t really try to hide it, as they occasionally actually tell you when they’re scheduled for trial.

That said, when I DO watch the news, crime is quite rarely, if ever seen as part of the show, so who knows. You’re not able to get a real good look at the situation when you don’t know how many have NOT made it to the other end of the receiver.

And yes, I do believe that people should be and are entitled to privacy of being arrested (ie the existence nor details of their arrest is not made public), and that just because you were arrested doesn’t mean you actually committed the or a crime at all. People are rather quick to judge based on what they hear and say, and those who didn’t even go to trial nor were going to go to trial are often treated as if they were simply convicted.

Sex Scandals/accusations are the most blatant, obvious, and publicly viewed instance of “hearing is fact”, enough so that people have called rape from TEN YEARS ago is as good in plenty to most people’s eyes as if they (actually) did it, and they did it yesterday in the parking lot to three people (which disgusts me frankly that people react and treat it like such without actually checking facts or even, making it basically modern gossip).

To say the least, if you fail to report a crime in a reasonable time (two weeks from time of discovery is extravagantly long for (nearly) any crime), and don’t have anything or there wouldn’t be anything to back it up (because said crime wasn’t actually committed), it could and should be dismissed as untimely, possibly with a record if there is in fact enough to suspect suspicious activity, but not enough to act on it. Whistle blowers need to have some staunch to their claims, and if not, their claims might not be able to be fully and properly investigated enough to produce an actual criminal investigation.

Sorry for the long and (politically) heavy post, but when a wizard’s got to rant, a wizard’s got to rant.

My original response got vaporized right when the next page posted, but tl;dr: it’s what you can be arrested for, why, by whom, and what the results of that should be that we ought to be more concerned with.

Cops make arrests and then write police reports.

Police reports get cited by trial lawyers, judges, and juries. They also are used by the media to write headlines.

In summary, the legal system, and the way it phrases its own reports, has in substance creative license over what the media reports – if the media is looking for sources from which to report “facts”, that’s often what it will turn to when it can’t get information on an incident any other way.

And when it comes to arrests, that is often the case, because police are frequently the first to respond to a scene, and low-profile arrests still become a matter of public record.

You know, the public records that I just indicated the press typically refers to as primary sources.

We can’t have a presumption of innocence in the media, let alone the public eye, when police and lawyer fillings get to choose the phrasing that the media simply parrots.

Sorry, I definitely need sleep. It is an oversight, that I left out the fact that all of the above has a tendency to leave cops and the rest of the legal system as the ultimate arbiters of truth, when any other witnesses to it are otherwise unavailable or presumed illegitimate.

Which is why we need to change what merits an arrest, imprisonment, and a trial, by significantly narrowing that field.

My original point was that, too many times, matters that should be resolved otherwise are left in these hands. So it isn’t just a question of privacy of arrest/trial/imprisonment, but the legitimacy of those things, as well, that we need to be rethinking.

In an ideal world, it would be our society that has the onus on it, to make a presumption of innocence (and do a great many other things for which this is also true) – but we live in a nation where that onus is, quite wrongly, on the law.

Because, for whatever reason, we put the law on a pedestal of morality more often than not – maybe because it had such a huge influence on our colonial infancy before becoming a nation, when “the law” was still “the king”? – we seem to relegate a disturbing and absurd amount of moral authority to the government, which has a sad tendency of abusing that power and our misplaced trust in it.

Whatever the reason for that is, it has had an effect on our thinking. Jurists walk into a courtroom and have the law judge-splained to them, because there’s a presumption they don’t know or comprehend what the law is (accurate, because of our misplaced trust in government). Corporations devote an apocalyptic amount of their attention and capital to ensuring that they just barely meet any legal requirements placed on them. And our national, preferred method of conflict resolution is litigation in court for anyone who can (or imagines they can) afford it.

Likewise, we learned during various wars – and the 1918 flu pandemic, which we seem to have forgotten – that the government likes to censor the press at its own convenience, and have taken this to simply mean that we can’t trust the press… as if that’s entirely the press’s fault, and not a result of the abuse of government authority (however corrupt it may mean certain segments of the press have been at various times, there’s still the fact that, in the face of military/Executive and Congressional power, civilian institutions understandably have very little backbone by default, especially when money is their main motive to begin with and political money is somewhere in their coffers).

This all adds up to a society that lets the government direct its moral compass, instead of the other way around.

I can’t begin to fathom what a world would look like where we take that power back, but enough said on that – that’s not the world we live in. It’s not a matter of “who deserves to be forgotten, and who doesn’t”, but rather, “why do we insist on consuming the news as a source of absolute truth, when doing so places our interests in jeopardy?”

This, I believe, is a question for our time, and for all time.

Excuse me. I clearly need sleep – that’s jurors, and not jurists. The former are our civilian opinion panels, the latter would be judges.

If only guilty people were ever arrested, if the police were capable of perfectly detecting crime with no false positives, there would be no need for a presumption of innocence, no need for trials, no need for privacy safeguards relating to the accused, no need for defence attorneys, no need for legal aid to pay them. The fact is, police and everyone involved in the judicial process are just people. They can and do make mistakes. Rights and safeguards, such as the presumption of innocence, are there to ensure the system fails gracefully, not to stop it from failing. And the fact that people you a priori don’t like also have these rights is no reason to want them weakened.

Just because a system can’t be perfect doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be improved.

Incidentally, I’ve no idea who “people” I supposdly already don’t like are, it would be real nice if you’d be more specific.

As a rule, I don’t intially like anyone.

I hope I did not totally misread you — let me know if you think so.

Well, the judicial system is, for better or worse, an attempt to remove human (mis-)judgement from the process. If there were no somewhat objective method to determine whodunnit and what to do with them, it’d basically come down to whatever somebody thinks of whatever they believe somebody else did…

None of that of course means that any country’s judicial system was working without flaws, and in fact we’re continuously discovering more and more hair-raising flaws not just about the judicial system but about how human brains actually work and how that affects that judicial system (eyewitness testimony is …. difficult, and “unbiased opinions” do not exist, anywhere, ever, because they cannot ) — but that’s of course still better than not having procedures.

I just think we should adapt those procedures to what is known. But change is hard, as anyone will tell you.

You’re not wrong.

As far as, for example, deploying a heavily-armed group of police who have never studied psychology (and have no certifications in it), to a scene where someone with PTSD is having a mental breakdown (who could easily be a former cop from another city, just to give these characters a little diversity), and having them break down the door with weapons drawn – my contention is that they’re perhaps not ideal reaponders for this particular problem.

Emergency dispatchers can send public utility maintenance when there’s a problem they specifically need to deal with, EMTs when there’s a medical issue, the fire department when there’s someone who’s trapped, fire, or certain other safety hazards that need to be addressed but no one is threatening violence, and cops… for vaguely any other reason. I know this from having briefly studied to be an emergency dispatcher. (Y’all don’t get paid enough for that work, if it’s your job, btw. Just saying.)

It’s that last option that’s a problem; cops have a very specific skill set, and it generally involves looking for and finding minute and even nonviolent legal violations – even when that’s not specifically the reason they’re responding to the scene. And they tend to respond to all of these carrying weapons and presenting a vaguely confrontational front, whether they’re brandishing said weapons or not, regardless of the context.

This is, to make an understatement of it, not generally appropriate.

I do imagine, however unreasonable this hypothetical might sound, that if we deployed EMTs to handle routine traffic stops, and social workers when there’s a domestic dispute (perhaps in body armor; safety first), the outcomes of most of these situations would not be negative, in the majority, for the civilians involved.

This is just a very basic outline of some of the problems with the system as it exists today, and it’s worse or better depending on where you live and who you are, but the point is, if it can be improved across the board, it should be – and we need to not only adapt some of the existing procedures, but revise and replace others.

There’s also plenty that individual members of society can do to avert the need to have emergency dispatch send anyone at all. Mandatory legal education in public schools would go a long way towards helping people know both their rights, and what the risks of misinterpreting the application of the law in some common situations could be. We certainly live in a litigious enough society that there are common situations, or conflicts, that could be avoided if nobody was quite as oblivious or ignorant as most people are.

Unfortunately, we expect the legal system to take full responsibility, trusting its agents to always be impartial, when – as Thrawcheld astutely pointed out – everyone involved are just people, and sometimes people do bad things despite being charged or legally obligated, even by oath, to do otherwise.

I’ve had a lonnnnnnng history of involvement with the legal system in the U.S. and have had both former judges, firefighters, cops, lawyers, and the like explain to me where there is clearly room for improvement, as well as civilian accounts of abuse, injustices, AND even a few cases where things worked out for the better because of the involvement of law enforcement. I tend to take these accounts as a whole, rather than letting their implicit bias guide my opinion, and view the system from the point of view of game development attempting to find bugs and exploits in the system.

So it isn’t that I have implicit biases myself that leads me to point out problems, but rather, the fact that I’m following the intuitive reasoning that a system is only as good as the effort that goes into building it.

Yeah, you clearly sound like someone who’s got a history with this topic.

And I think you make a bunch of very good points. Particularly some of the stories which make it across the ocean from the US are frightening.

I think it is to some extent impossible to avoid having “the law” replace “morality” because the spirit of a law can’t really be precisely defined, but a law needs to be written in a way that people, even ones who don’t like some particular law, who follow it to the letter will act in whatever way is deemed appropriate. I think that actually many of the issues with law enforcement or judges not following the spirit of the law stem from initiatives which tried to remove bureaucratic hassles and permitted police to “follow their instinct” more — which might work for some individuals but is not a good idea for some others who maybe don’t have the type of instinct you’d want to have in somebody with a gun and authority over others. So in some sense, I think the issue is trusting the “character” of everyone in law enforcement more than insisting on procedures and criteria. That then includes trusting the testimony of a law enforcement officer more, even when the question is whether they committed a crime, than the victim of that crime. Such errors are based on poor human judgement of character, and on not following procedures which were trying to reduce the need for that.

I think I agree with you that it would be absolutely desirable to have a world where “the public” (that is: a significant part of the population, and the general consensus among most people) follows the spirit of the law. But in court cases etc. you cannot achieve this. But that means that somebody who barely cheats themselves past the criteria for illegality has an advantage over somebody who respects the spirit of the law and keeps a safe distance from such things. Over time, corporations and powerful people in particular (but many others too) will learn to do this because they stand to gain from it, and thus it’s almost unavoidable that some portion of the population will simply ignore morality and only heed the letter.

It greatly upsets me when people start talking as if that was a good thing.

To extend the notion from last page that this is encounter has a flirtatious vibe “How would you like me to solve you, gently, or otherwise?” with that expression, is a line with a lot of different energies behind it.

Politics aside, I think Carol just made a gigantic mistake by calling Shanna “a problem” and there being resources available to “solve her” — that’s not just a pretty direct threat but also a straightforward admission that she does have something to hide, and very much wants Shanna to stop looking.