Annotated 50-4

“There are three deaths. The first is when the body ceases to function. The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that moment, sometime in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time.” — David Eagleman

“There are three deaths. The first is when the body ceases to function. The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that moment, sometime in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time.” — David Eagleman

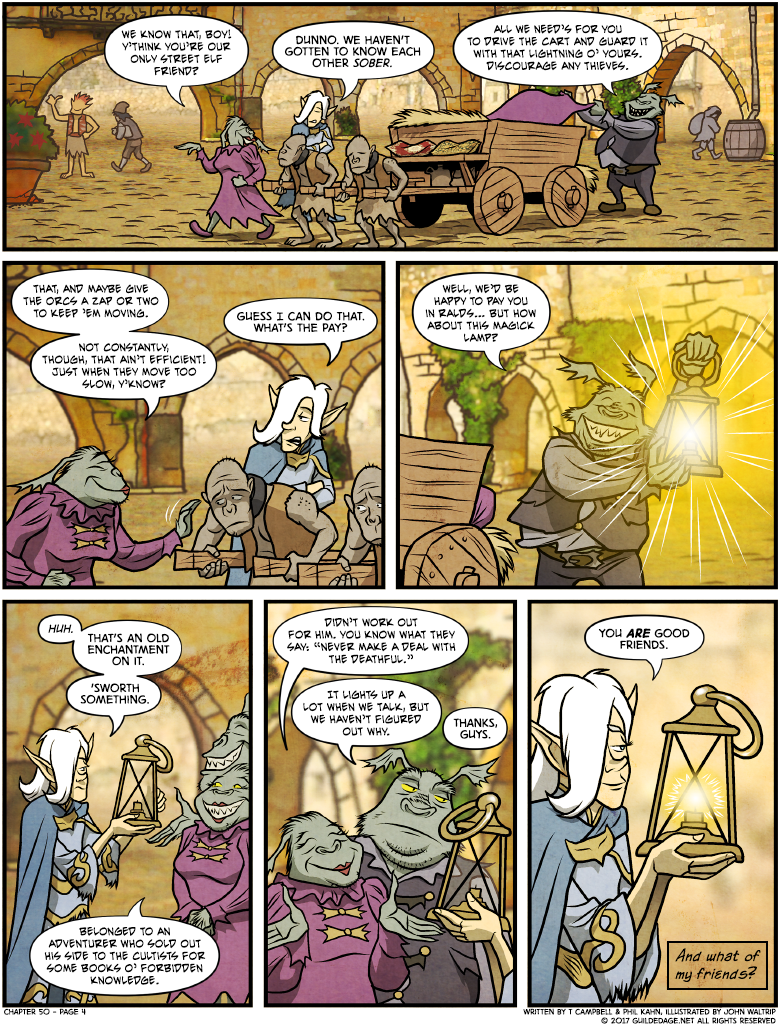

So here we tie up the loose end of Lectrus, last referred to here (and confirmed dead here). I wonder how many readers thought we planned to resolve his arc this way all along? We didn’t, but I like how it shook out: it’s a mere wrinkle in Jemmington’s story but a macabre end to Lectrus’s. His name isn’t spoken here, but otherwise this feels like Eagleman’s “third death” for him: this is the last time he will have his own story told. Jemmington seems unlikely to even remember the tale of the book-loving adventurer, and the goblins are only using it as a sales pitch. Lectrus might be mentioned in passing in one or two of E-Merl’s, Sundar’s, or Byron’s remembrances, but just as a footnote. Let’s tag him here, just for the sake of it.

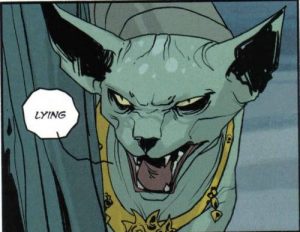

ICYMI, the lamp glows brightly at Goblarry and Goblily’s lie that they’d be happy to pay in ralds instead of a trinket with no obvious value. Jemmington’s description of them as “good friends” earns a smaller glow because it’s a smaller fib. He understands they’re using him, but everyone uses everyone, right?

When we first presented this lamp, we weren’t clear on whether it only illuminated lies told by those who knew better, deep down or otherwise, or if it was more like a tiny winter elf in a bulb that could tell you if anything was true, regardless of the beliefs of the speaker. When the lamp is shown again later, it’ll be clear that it’s a lie detector. So the points where it lights up will say a lot about what lies Jemmington is telling himself.

FB: It’s like if Antiques Roadshow were literally filmed in the middle of a road.

I like that they never figured out why it lit up when they talked (as evidenced by the fact that it didn’t when they said that)…just shows lying to be so natural to them they don’t even notice when they’re doing it.

I bet Goblarry doesn’t even consider it a lie to say “We’d love to pay you in Ralds but how about…?” That’s just his standard phrase to express “I don’t want to pay you in Ralds”, but in a more polite way.

I mean, technically, he doesn’t even state that he didn’t have the Ralds to pay Jemmington, he simply suggests to give him the lamp instead of money. The only not-quite true statement is that he would love to pay in Ralds, but taken literally, that statement is undecidable because it does not include the conditions under which he would love to pay.

The fact that the lamp lights up anyway might mean that there actually *no* conditions under which Goblarry would prefer giving money — or that I’m overdoing it again :)

Either way, I’m pretty sure Jemmington has learned enough about Goblin culture to read the sentence correctly, independent of what the lamp does.

One thing we can confirm from later data is that the lamp lights up when the subject is telling a lie that they don’t know is a lie on a conscious level. So yeah, Goblarry might not be thinking much about his statement. “That’s just something you SAY, you know, like when you pretend to care about how people are doing!”

But I think you can Occam’s-razor the conditionals of the statement. If my wife says “I’d love to watch that movie,” she’s talking about a certain time frame, not inviting me to start playing it at 1 in the morning or promising to blow off work to see it the next day. So the only conditions that matter, I think, are the ones right in front of them. If all the swag they were moving was highly valuable to them, then they would indeed love to pay in ralds, as that would save them money in the long run. But a lamp that lights up randomly (and doesn’t stay lit) is of little use to them. If they didn’t know it was a magickal item and therefore interesting to the right buyer, they would’ve discarded it already.

I guess that’s where the intricacies of language come in:

I interpreted “I *would* love to” as “If were true, then I *would* love to do X, alas, is not true”.

In this scene, he’s of course hoping that Jemmington interprets that condition as “we have the necessary cash for it”. In Goblarry’s mind, the condition is probably “I have nothing else to offer that I value less”, and it is almost never true — but it would still make the sentence readable as not a lie.

That’s of course a much more literal reading than yours (which I suspect is closer to how most native speakers perceive it), which is “This is my preferred thing to do/I feel like doing it” — which makes the sentence from Goblarry absolutely a lie, of course.

I guess that all means that

a: I *am* overdoing it :) (of course I am, that’s kinda my thing…)

b: the lamp reacts to the intended/implied meaning of what somebody says, or possibly to the (conscious/subconscious) *intention* to deceive rather than the strict logical interpretation of the language used. Which makes sense, and makes the lamp a lot more useful because that makes it a lot harder to lawyer your way around it.

I guess writing the extended adventures of Lectrus might have become hard at some stage because you’d have to nail down all those properties of the lamp. There’s a continuous spectrum between saying something that’s literally true but potentially misunderstood, to something true but intentionally misleading, to some trivially true statement that implies false premises (intentionally or not, or kinda maybe a little… a huge favourite in present-day propaganda), then there are the kind of non-statements which PR-spokespeople love to make … and that’s before lawyers come into the picture.

I mean: Whether “fine, thanks!” in response to “how are you” is a lie, mostly depends on the recipient: To some, it is merely the expected thing to say, according to protocol, and any other response triggers the “oh no, something’s wrong!” protocol, but to others, it is very much a lie(*). And what if one of both types of person is in the room? Politicians know that the same sentence can be perceived as very different statements by different people…

…actually, I think I’d totally read a story that explored these concepts, but I can’t imagine how an “objective” truth indicator in such a story could work without ruining it.

(*) as in: it took me years, and I still have to take a breath before responding with a straight face “…I’m alright”, and prepare to assure the other person that they really don’t need to worry about me, at least not more than about everyone else, while trying to avoid the word “worry”, because I really think I’m not doing worse than the average person around, it’s just not entirely fine, because nobody is completely fine most of the time.

Except sometimes, when things are in fact great, and then I can’t keep from explaining *that* because if things are really great for a change, then that needs to be mentioned. But I feel like I’m probably not supposed to do, either…

This is an aspect of English that native speakers don’t often consider, I’d imagine. I’m not sure what you’d call it, except a “hypothetical alternative,” maybe.

A comparable situation would be me telling my tired wife, “We could cook up something out of the freezer tonight, or…how about I grab Chinese?” In that situation, I am perfectly fine with the first option, but I present the second option with more enthusiasm. That reflects my knowledge of Janice more than my own desires: when she is tired, grabbing Chinese is a good way to get us fed without having to do any work. I feel like I’m helping her out by mentioning that option and offering to get the food. If she surprises me and goes with the first option, though, I’ll still be perfectly happy. I’m easygoing like that.

Goblarry with Jemmington is pretending to be like me with my wife. What he’s telling Jemmington is “(1) We have two options to pay you and (2) we’d be happy with either option you chose, but (3) I really think you’d like this second option better and (4) it’s probably more valuable than the going rate in ralds, in my estimation!” (1) and (3) are true, (2) and (4) are not.

To the rest of your comment: Yeah, there’s a lot you can do with a MacGuffin like this. We only had so much time to explore it, but it did help ensure that our last action set piece would have a little liveliness and resonance.

I suspect the lamp simply isn’t calibrated for social white lies. It was intended for use for interrogation, oaths, and other statements whose truth was important. So it wouldn’t have mattered much to its makers if it lit up for “Oh, sorry, I have a thing.”

Jut an FYI. The link “here” is pointing back to this page.

Well, it’s technically correct. This page *is* the last time Lectrus will be referred to. :)

The last bits that are known about his fate (which I had expected the link to direct to), are here:

http://guildedage.net/comic/annotated-36-8/

He ran off …

http://guildedage.net/comic/annotated-41-10/

…and died at some point, because Gravy sees his bubble in the afterlife.

My guess would be that he ran into some cultists and/or berzerker spirits on his way out of that lumber town.

Yeah, fixed that, sorry!

Oops! Got it, thanks!

I like the small nod to Goblaurence’s views on “efficient orc punishing”, and that this page makes it extra clear, how it’s not coming from any consideration for the orcs’ wellbeing. It’s purely for the benefit of the slavers.

Good thing Bandit is working on the issue (in her own way), since orc rights seem to still be far away in this world.

“Never make a deal with the deathful.”

A stealth pun that deserves a groan! ;)

I also really liked that one.